To Be…and To Be Again

IN THE INAUGURAL season of the Harlequin Players, in the summer of 1965, I drove to the St. Mark’s campus every day in a white, stick-shift (unsafe at any speed) Corvair, with Sonny & Cher on the radio singing “I Got You Babe.” The counterculture was underway, along with the war in Vietnam. Boys were letting their hair grow out over their foreheads, like Sonny and the Beatles. But whatever the length of your hair, you did not want to be late to 10600 Preston Road because the Oxbridge-accented director of the Harlequin Players, an intense young man of unquestioned authority and sophistication, had made it absolutely clear that military punctuality was Rule #1 in the theatre, inviolate. And you didn’t want to displease him or offer a shred of evidence that you were unworthy of his company and respect.

I found myself recalling Mr. Vintcent’s demanding regimen all too vividly on a recent Saturday morning as I drove to the St. Mark’s campus for a rehearsal almost five decades later, worried that I was going to be late for the nine o’clock call. I told myself to relax, it was a reunion weekend after all, and this was merely a staged reading of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood, the play for voices (and a large cast) that Harlequins did twice in the eight seasons Vintcent presided over his youth corps. Nine a.m. on a Saturday. Could it really matter if we were a little late?

Mr. V.

No sooner had I walked into Decherd Performance Hall, than I heard that voice. “Where is _________? And where is _________? Surely she’s coming?” The tone was not quite accusatory yet carried a familiar, stern impatience. The sound of Anthony Vintcent had not changed appreciably in 47 years. Except for the new setting of a modern proscenium theater with a big hardwood stage that loomed behind him, all was as before. Harlequin alumni, now in their 50s and 60s, many returning from the east and west coasts for the weekend, palmed bagels and cups of coffee as they turned in deference toward the director who was about to tell them how they were going to prepare in one rehearsal for the 2 p.m. public performance of Under Milkwood.

“Consonants,” he said. “Please remember the consonants. They’re important.” He crisply enunciated an example with an emphasis suggesting we were rehearsing for a national broadcast of some kind instead of for a small audience of family and friends. No doubt Vintcent would have said, “Why should there be a difference?” That was the mark of Harlequin Players, looking back – that Vintcent treated us like young professionals.

For the 70 some-odd Harlequins assembled here and especially for the 16 onstage, the past was undeniably present. Sure, our bodies had aged and people looked different. The boys’ long hair was either missing altogether or in some cases even longer but a different color. Vintcent himself, now 75, was bald on top, with a healthy white beard. Yet we, all of us, were easily swept back in a matter of minutes to distant summers when we had learned so much from this man and from each other. How, exactly, did this happen?

It seemed improbable that such fuss was being made over a high school drama group decades after its last curtain call. Who would believe it? At the packed luncheon in Vintcent’s honor on Friday at St. Mark’s, current faculty and staff must have wondered what it was this wandering Canadian could have done to inspire the loyalty evident at this grand homecoming. Since theatre – unlike film, painting and recorded music – is evanescent, leaving nothing behind but programs, photos, reviews and memories, the experience of the Harlequin Players is measured today through the fond recollection of those who lived it, becoming the stuff of folklore.

The energy powering many of the finest theatre companies expends itself as if by natural law, which is what makes the heyday of any theatre group, even a high school one, something to relish and celebrate. I doubt any of us, when we were 16 and 17, had a clue about this, but the size of the gathering here offered proof that many of us understood it now: that we took part in something that was special in a particular time and place, and we are grateful to Vintcent, to St. Mark’s and to the moon and stars.

IN AN ARTICLE I wrote for the Dallas Times Herald when Tony returned to Dallas to direct a single production of The Happy Time in the late 1970s, I recalled how he had once projected the sort of charisma normally associated in Texas with winning high school football coaches and unthinkable for a stage director. At St. Mark’s, where he also ran the Fine Arts Department and directed plays during the school year, he cast All-Metro-Dallas linebacker Tommy Lee Jones as the narrator (or First Voice) in the first production of Under Milkwood, which proved a revelation – maybe to Jones but certainly to many at the school. Dylan Thomas? Welsh poetry? That kid from West Texas? How was this possible? Legend tells us it happened. Some of us remember.

Janet and Tony at Blue Mesa Grill

Jones was not in the summer group (where Tony himself read the First Voice, as he did at the reunion performance), but Jones’ eventual celebrity reflected back favorably on the milieu Tony created, spanning the St. Mark’s drama club and Harlequins. Perhaps because Tony cultivated a professional attitude in us, it’s no surprise that a fair number of Harlequins later did find their way to grownup stages in theatre, film and other creative pursuits. Mark Capri, back to read the Reverend Eli Jenkins so damned beautifully onstage at the reunion, at one point toured with the Royal Shakespeare Co.; Pat Richardson became a TV star on Home Improvement, Gary Pearle directed plays at Washington’s Arena Stage and on Broadway. The late and much lamented Bill Hootkins made a career for himself in the London theatre and appeared in films with Ned Beatty, John Malkovich, Warren Beatty and Brando. Ann Armstrong achieved acclaim as a top-drawer blues singer and guitarist; Frances Aronson became a lighting designer on and off Broadway, Jenny Burgess a leading actress at Dallas’ plucky Stage #1, Kimberly Webb a fixture at Berkeley Rep, Jerry Carlson and Ronald Wilson professors of film studies, Fran Burst a documentary filmmaker. I drop these names reluctantly, knowing that I’m leaving out many more who achieved distinction in the arts and elsewhere, but even this short list might suggest that something was happening here all those years ago, something ignited by Mr. V., as some called him.

There were more than 200 Harlequins in all, and some have now left us, as we were soberly reminded by Mr. V. at the dinner Saturday night at Blue Mesa Grill. Those of us still on the planet were asked by the reunion organizers to write personal letters to Tony, to be collected in a binder and given to him, each letter spelling out what he and his summer theatre meant to us.

I wrote that I doubted he could have given much thought to the possibility he was educating a future drama critic that first Harlequins season but that is the career path I took at one point. And without question, my own sense of what theatre could be or not be was influenced by him, his mind and intuitive method, his belief in the quasi-religious purpose of what we were up to. I remember how tireless he was in what must have been a daunting task, coaxing mumbling teenagers (me) beyond our limitations into a realm of believability as demanded by the text. You wanted to be good enough not to let him down. I think that was a big part of it. And he didn’t do it through fear or intimidation. Instead, he insisted that you climb up to the place where he was standing so you could get the same view.

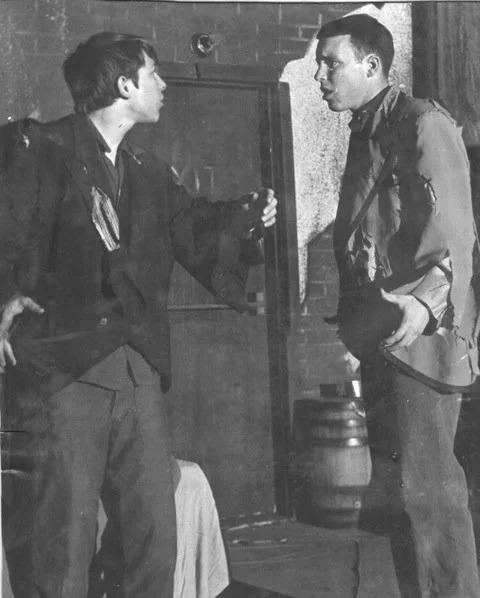

I told him he showed me a side of myself I did not know existed. At 17, I was more interested in sports than putting on costumes and pretending to be someone else; I wasn’t sure I wanted to do this at all. But my parents urged me to try it, and how can I thank them enough for that? Once I was in the room, I had no desire to leave. It was way too interesting. And I got to play a tender-hearted prize-fighter in the first production.

The St. Mark’s campus today is nearly unrecognizable from the one where we spent that first summer. Architecturally more distinguished it is, to be sure, and the Decherd Performance Hall seeming as Lincoln Center compared to the tiny black box where Under Milkwood, The Cave Dwellers, The Happy Time, The Cherry Orchard, The Lion in Winter, Oh! What a Lovely War!, The Madwoman of Chaillot, Uncle Vanya and so many more were produced.

Yet sitting onstage at the Decherd during the Under Milkwood rehearsal, the air-conditioning so effective we needed long sleeves, I suspect some of us missed the old space, where we might have communed more easily with the ghosts and spirits that plays leave behind. The Harlequins theater was air-conditioned, sort of. Outside, the nights were so hot and muggy you could have walked down Preston Road naked at 2 a.m. and still felt warm.

The author, right, in The Cave Dwellers, with Kimberly Webb

That image in fact occurred to me late one night after a show, a sign of imminent debauchery or merely a symptom of the sensory expansion released by the whole experience, evidence that theatre was not something you only saw with your eyes and processed with your mind but felt on your skin. Tony talked about ritual and ceremony, and on that night, alert and sleepless, I felt I understood for the first time what he meant and how our little group was connected to some larger, eternal human need to act out stories in order to claim our place on earth, as primitive peoples had done, maybe even here in the jungle heat of north Texas summer.

When she introduced Tony at the luncheon Friday, Janet Spencer Shaw, the former Hockaday teacher, Harlequins’ managing director and “queen,” looked out from the podium and asked why all of us were here. Then she speculated that we must be members of the same tribe who had found one another long ago.

Her words hurled me right back to the epiphany of that steamy night in 1965, and they felt oh so true. Saturday we were onstage again, the tribe gathered around the warmth of Dylan Thomas’ rhythmic poetry and our leader, who reminded us how lovely it could sound, how lovely he could sound reading the First Voice, describing all manner of timeless creatures inhabiting a Welsh coastal town, indeed taking us there. Tony told me once that acting frightened him, and that’s why he became a director. It remains a statement I must take on faith, for with his voice, intuition and talent, of course he could have been a successful actor – at Stratford, in New York or Hollywood. Instead, he gave himself to us, and all these years later I think we are still trying to prove ourselves worthy of his devotion.

The rehearsal ran four hours with a short break. Unlike Mark Capri, Jenny Burgess and others who were pros, I had to be reminded I was not projecting (oh, that). At 2 p.m. the lights went to black and a remembered anticipatory silence filled the hall. At last, a spot came up, stage right on Tony, at one end of our readers’ semi-circle. “To begin at the beginning,” he said. “It is spring, moonless night in the small town…” The ritual had started one more time, and who among us wished for it to end?