The Letters of Tom Adams

TOM ADAMS WAS ALREADY DREAMING of becoming the head baseball coach at St. Mark’s when he sent me a letter from his boyhood home of New Canaan, Connecticut in the summer of 1964. “I’m hungry for that job,” he confided, sharing his eagerness to move up to the varsity along with players he had coached on the JV team during his first three years at the school. He said he had done “considerable thinking” about this and scribbled a prospective lineup:

1) B. Kohler c 2) MacAdams cf 3) T. Kohler p

4) Rozelle 3b 5) Mitchell ss 6) Nobles 2b

7) Lucas 1b 8) Baldwin rf 9) Heyer lf

“If Olson pitches,” he went on, “T. Kohler goes to 1b and George bats 9th, with Baldwin and Heyer moving up to bath 7th and 8th.” All eventualities considered! He couldn’t help himself. And he had Rozelle batting ahead of me?

“Don’t show this to anybody,” he added. He was 26 and aware that the current varsity coach wasn’t stepping down.

I remember all the players in that lineup, but I don’t remember the letter from 56 years ago. It’s one of 14 that I have from him — hand-written on 6×8 manila-colored stationary — representing our correspondence over my schoolboy summers starting in 1962, artifacts from a previous era of innocence and trust between teachers and students. I stashed them in a box and hadn’t looked at them again until recently, after he died in Dallas at the age of 82.

14 Letters from New Canaan

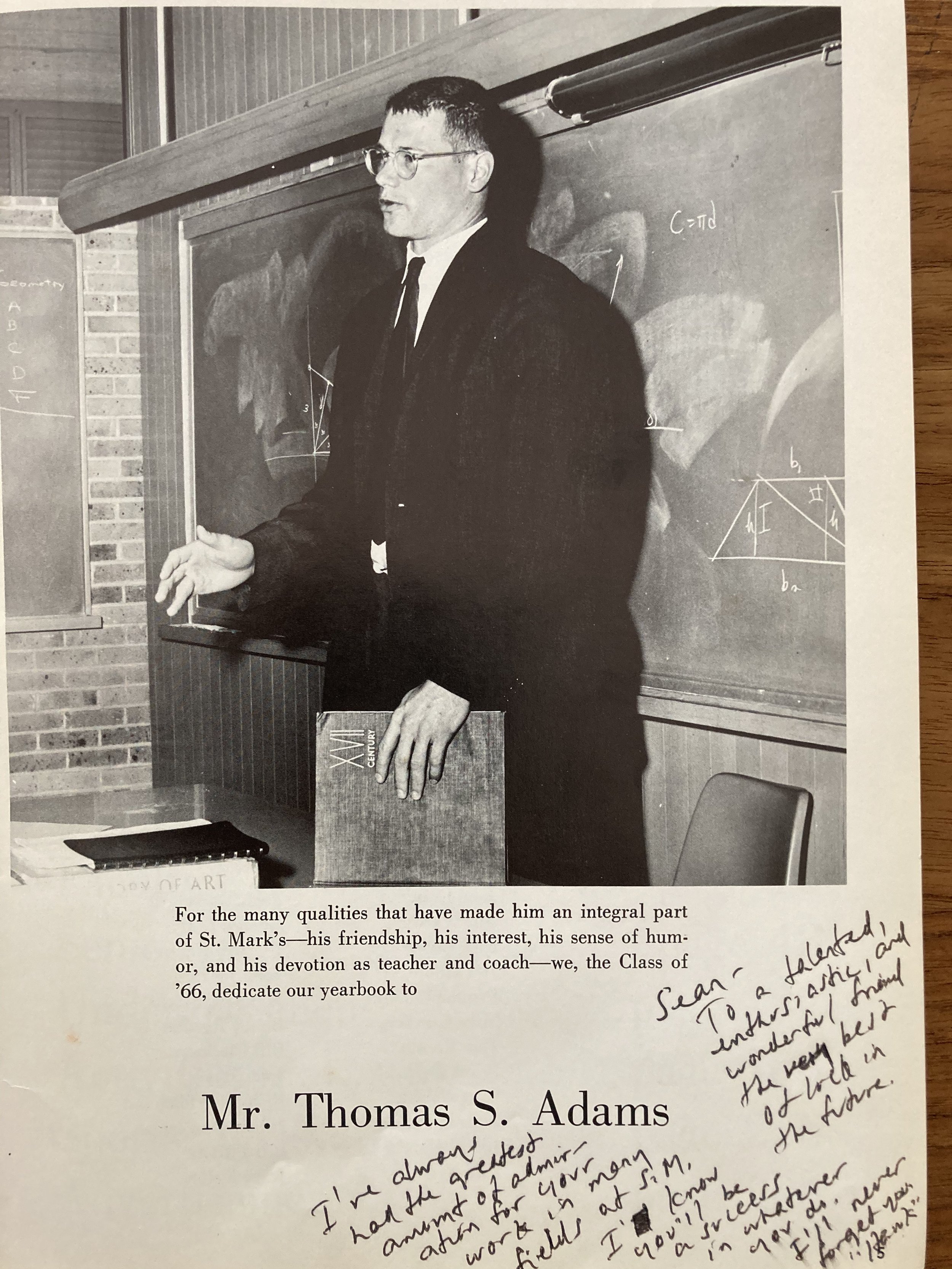

IF THEY WERE TO PUT UP a statue to anyone at St. Mark’s, it would surely be to Tom Adams, a teacher-coach with a panoply of uncommon talents and a personality that was part scholar, part play-by-play announcer, an art historian who was also a one-man Elias Sports Bureau. He arrived straight out of Princeton in my eighth grade year and stayed almost half a century, offering instructive attention, laugh-out-loud irony and friendship to thousands of students through the years, including me, back in the beginning.

As that 1964 letter suggests, he was not just a young history teacher relaxing back home over summer break but a man possessed – possessed by the organizing principle of sports and the puzzle pieces of teams, in particular the San Francisco Giants but also a school team he likely wasn’t even going to get to coach (yet).

“I’m sorry, but I’m hopelessly in despair now and am incapable of writing a decent letter,” he said before promising to write again soon and signing off with his customary “Sincerely, Mr. Adams.”

His despair had to do with a series of losses suffered by the Giants of the National League to whom he had pledged allegiance and entrusted his happiness since growing up with them as the New York Giants before they moved west in 1958. He was 13 when Bobby Thompson hit his famous home run against the Dodgers in 1951 to win the pennant, “the greatest moment in sports,” he assured me.

Mostly that’s what he wrote about in the letters: the Mays-McCovey-Marichal Giants, whom he followed with tireless devotion, sharing his thoughts, joys and complaints, offered sometimes with ironic hyperbole and what would later be known as trash talk. “Did you notice how the Dodgers went into an immediate tailspin as soon as their ‘invincible’ Koufax lost to Pittsburgh? He’s their leader, but he’s only second best to Marichal who could easily have 20 wins right now.”

HE ALSO PROVIDED REPORTS on the American Legion team he coached every summer in New Canaan. “The American Legion team is 6-8 with 4 games left in the next 7 days. Lack of hitting is the big problem.” And there were his experiences in softball and basketball leagues, plus the occasional golf tournament. He often shot in the 70s. He was Sports Center before there was Sports Center.

I have little recollection of what I wrote to him, but his responses indicate it was mainly about baseball, the center of my universe then. That was our connection. At the time I had not heard of Ring Lardner, but Mr. Adams was like having Ring Lardner as a pen pal. I never had him in class, yet his erudition and playful irreverence surely influenced me, a fledgling sportswriter and student athlete with the ambition to follow in his footsteps and go to Princeton, where he had earned letters in baseball and basketball. He scored 14 points in a first round NCAA Tournament game against Duke. I wondered how he missed being a Rhodes Scholar? At 6’4”, with his square jaw and long-legged build, he looked like he could be pitching for the Giants or playing for the Knicks.

In July of that first summer of 1962, as I was heading into 9th grade, he wrote, in a familiar non-cursive lettering: “As I tried to tell you this spring, Sean, this San Francisco club is now an experienced, mature club that is not going to be seriously affected by a slump or even a key injury, unless it be to Mays.”

A MONTH LATER, in August, he related how he “got killed” in a play at the plate in his softball league when “the catcher’s knee got me right in the ribs as I slid, and I could not play golf at night until Friday.” (He neglected to mention whether he was safe or out.) He closed with, “I hope everything is well with you and your parents…I certainly have enjoyed your letters this summer and any others, of course, will be appreciated.”

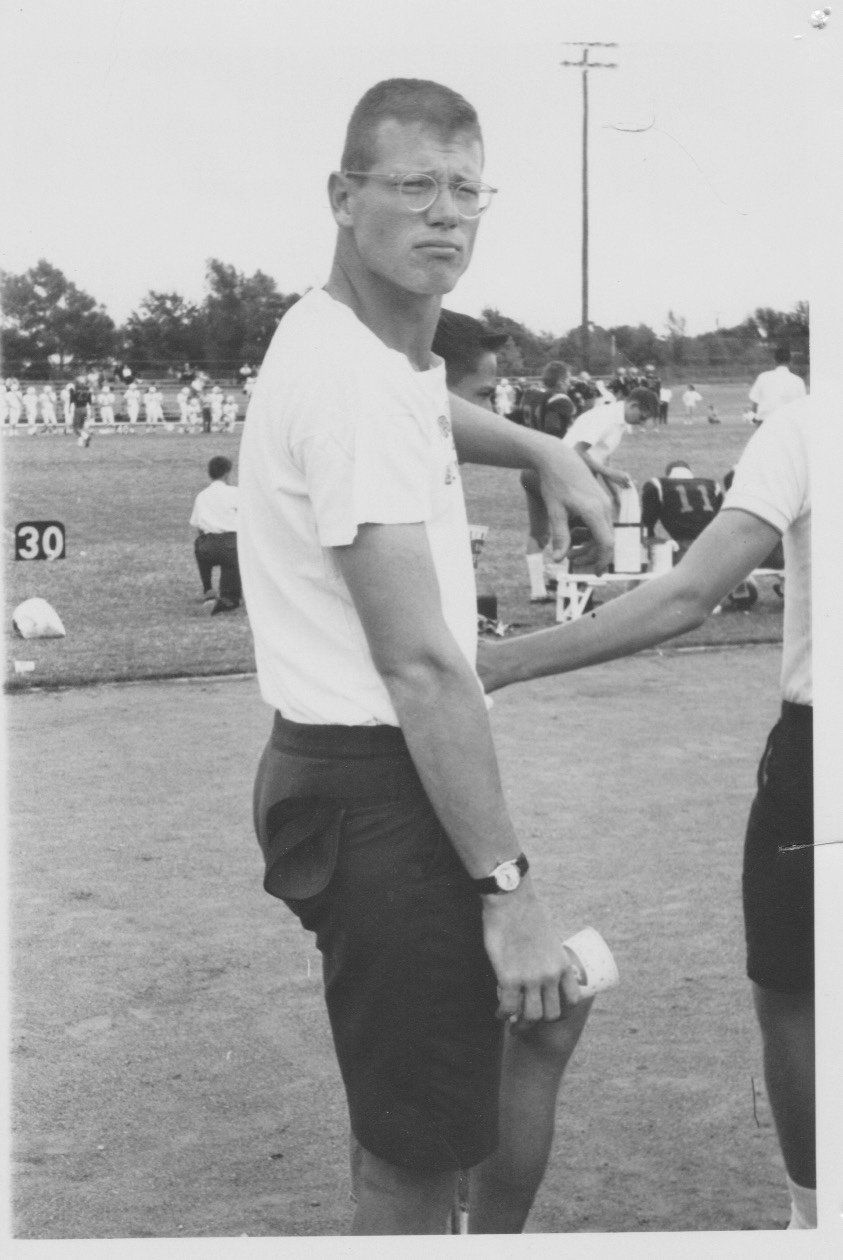

Coach Adams in 1962

The next summer, 1963, with him back in Connecticut, we exchanged six letters. His included such observations as “I guess it goes without saying that the Giants have made me sick, and today’s postponed doubleheader with Pittsburgh just prolongs the agony and frustration.”

There’s nothing here about contracts or salaries, sabermetrics or Willie McCovey’s launch angle (which would have been impressive). The game was simpler and less about money, like the country itself.

“I just had to let off a little steam, but keep one thing in mind – S.F. is going to come back yet despite their many problems, mainly their infield which has been totally inadequate both at bat and in the field – I mean, the whole infield, too.”

The record shows they did not come back.

“As for the American League, forget it – any league that cannot begin to pick up ground on the Yanks minus M&M [Mantle and Maris] must have some feeble teams.”

I must have sent him MLB all-star picks that didn’t include a sufficient number of Giants because he responded, “I won’t bother to comment on your biased viewpoints regarding the all-star selections. When you decide to look at things objectively, I’ll consider your opinions worthwhile.” Ha. The bite of his signature sarcasm, which I had learned to enjoy and not take personally.

THAT SUMMER, HEADING into my sophomore year, I was deliberating whether to continue with football, considering myself undersized for the varsity, and evidently I asked his opinion. He had been the assistant coach of our overmatched 9th grade team that finished 0-6, with me as quarterback. “You have a lot of ability in football, Sean, but your size may work against you in the long run, and you’d never feel it was really worthwhile hanging on. I hope that doesn’t discourage you if you want to play badly…I feel that you’ll be making a good decision either way.” Diplomacy, thy name was Adams. Come September I opted out of football.

No Curves, Please

He reminds me in the letters that I was playing golf in the summers before high school, and he was encouraging me. I have only the faintest recall of this and also why I gave up golf until decades later. I’m pretty sure I had never played with him until the St. Mark’s alumni tournament in 2011 when he announced to our struggling Class of ‘66 contingent in his best Les Keiter voice, “OK, on every hole from here on, we’re going straight for the flags.” Which was hilarious at the time and an uncanny flashback to the weekend afternoons of our youth playing touch football, softball and tennis with him while he offered dramatic play-by-play commentary.

HE SOUNDED LIKE NO ONE ELSE, practiced in the locutions of academic authority yet captivated by the archness of old radio melodramas and the squawk of the press box. He invented an eccentric theatrical persona for himself as “The World’s Fastest Talker,” brought to life each year in the school talent show. In top hat and tails he would emit at incalculable speed a torrent of words representing the names of all 50 states and their capitals, the 66 Books of the Bible, the alphabet backwards, the 28 train stops between New York and Chicago the 32 points of the compass and more, his mouth galloping to a finish in under 1 minute, stopwatch in hand. It was both amusing and astonishing.

Tennis was not really his sport but he was often available to play doubles on the courts at school, always bringing along a transistor radio to monitor the baseball scores provided at regular intervals on WRR. If a Giants game hadn’t been updated in a while, he would frown and utter ruefully, “The Cards have been up for a long time in the sixth.” A stony stare conveyed the message: “Don’t you boys realize what’s at stake here?”

Dallas didn’t have an MLB team then, but the Astros were in their infancy and, more important, were in the National League, meaning the Giants had to visit Houston a few times each season. No way he was going to miss those opportunities, and in the spring and fall he hauled carloads of Marksmen down US 75 to see our first major league baseball.

MY SINGLE MOST VIVID MEMORY from all those games was sitting down the right field line once and seeing Felipe Alou, the Giants’ right fielder, scoop up a single and fire a long strike all the way to 3B to cut down a runner trying to advance from first. From our vantage point right behind him, the ball soared all that distance as if catapulted from a rocket launcher, straight as an arrow and almost as fast. OUT! It was an up close and personal revelation you couldn’t get on TV of the athleticism of big leaguers and what they were capable of. I can still see it.

“Speaking of S.F.,” he wrote in one of those early letters, “they’ve been in their usual June slump of late, but don’t worry about them, Sean, they’ll bounce back on top in due time. I hope you’ll be ready to watch them clinch the pennant in Houston in late September.” I’m not sure any of us became Giants fans, but the trips with him were a blast, playing 20 questions in the car and making up athletic contests for the motel pool. Competition always.

Only one letter in 1965 and a comment about that Houston team: “I notice that the Astros are back to normal – just throwing in the towel game after game. The idea of starting Dierker and Cuellar in a doubleheader against the Phils today is absolutely ridiculous – they might as well not even bother to play the games.”

SENIOR YEAR, WHEN COACH BROWN had a meltdown during our final home game and disappeared, Mr. Adams stepped in as third base coach, travelling to Austin with us the next day for the conference tournament. I think most of the team welcomed his presence and wanted to show our feelings by winning the SPC title. That did not happen despite his best efforts: in one game he was able to read the opposing pitcher’s body language and flash a sign to the plate when a curve was coming. I still couldn’t hit it.

Princeton Man

In the end I didn’t apply to Princeton, and in the summer of 1966, before I left for a different east coast college, we exchanged two letters. He was in graduate school at Harvard (though commuting back to New Canaan to coach his American Legion team). “Another half-assed baseball season draws to a close,” he said tellingly in his last letter, postmarked August 17. “The Giants are almost as bad as the Yanks. Herman Franks, who I thought did a good job in 1965 [as manager] has gone to pot this year. His best players sit on the bench half the time.”

MR. ADAMS WAS LEAVING ST. MARK’S for what would turn out to be a brief sojourn at Albuquerque Academy before returning to 10600 Preston Road for a run of 47 years, during which he would get that head coaching job in baseball and win 15 conference championships, plus six as head basketball coach. Before he retired in 2011 he received seven yearbook dedications, starting with our class of ‘66.

I wonder now if I ever really knew him? He was the greatest of characters who often seemed in character, more comfortable onstage than off. He once narrated an imaginary title fight between Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba and Laotian prince Souvanna Phouma, but he was reluctant to talk about himself — beyond the measure of sports. In those years, in those letters about all things athletic, it didn’t matter. He was smart and funny, considerate and edifying.

“On my way to Albuquerque,” he concluded the letter in his regular blue-penned script. “I’m going to stop in Dallas Thursday nite Aug. 31 and stay for a few days. I’ll see you on the court.

“Sincerely, Mr. Adams.”

I wouldn’t have missed it.