My Mother, Lu Mitchell

Lu Mitchell, my mother and satirical songwriter, died March 25 at the age of 95. A memorial service was held May 5, 2019, at Sons of Hermann Hall in Deep Ellum. This is the eulogy I delivered.

“MOM” – the word might sound odd when attached to the name of the woman who wrote “The Night John Bobbitt Lost His Weeny.” I was reminded of this when one of her musician friends said to me, “I keep forgetting that when you refer to ‘Mom,’ you mean Lu.” True enough.

At KNON Studios in 2013

IT’S HARD TO REMEMBER when Lu – that is, Mom – was not a performer and something of a public person. We presume she was born a performer, though her working class parents, Irish and Hungarian, were not musical or theatrical. She found her voice singing in Girl Scouts, and in her early 20s discovered acting at the Bethlehem Civic Theater in Pennsylvania, where she met and married my dad, Gene, a director and playwright. They both had day jobs at the Bethlehem Steel Company – not a place that encouraged creative types. They needed something different and in 1949 took off for Texas after seeing an article in Holiday Magazine promoting the new Southwest. They didn’t know a soul here. Dad originally wanted to go to Vancouver or San Francisco, but Mom hated the Pennsylvania winters and insisted on someplace warm.

Those first years in Dallas – South Oak Cliff, in fact – were not just warm but a scramble to make ends meet, with no time left for self-expression beyond the occasional charades party. The turning point came when she met Hermes Nye, a lawyer and writer who played the guitar and sang old English ballads and cowboy songs. Mom wanted in on that right away and started taking guitar lessons. She and Hermes and a couple others founded the Dallas Folk Music Society and helped bring Pete Seeger to town when he was still blacklisted.

Something was in the air, the times were a changin’, and because of Mom, I was surrounded by it – albums by the Weavers and Judy Collins and Bob Dylan, plus the hootenannies, where she and other grownups strummed these big, beautiful Martins and Gibsons, transmitting songs that settled in my soul. The music seemed important and different from what was on the radio. It was full of history and the blues, storytelling and poetry – and righteous. Songs about the struggles of the common man, the Civil Rights movement and against the War. Lu and Gene had left the Catholic Church, and the three of us happily became Unitarians. If someone had asked me then what kind of music was played in the Unitarian Church, I would have said Woody Guthrie and Odetta. Folk music and Unitarians seemed to go together.

AT THE TIME, I took all this for granted, as a kid does. Only later did I come to appreciate what a gift it had been. She also taught me to play the guitar and banjo and even allowed me to back her up on occasion — when real musicians were not available.

She didn’t want me to play football – evidence that she was not a native Texan. “It hurts me to see you lying on the ground like that,” she said after watching me get crumpled as an undersized quarterback on the 9th grade team at St. Mark’s. To spare her further angst – and there might have been other reasons – I gave up football after that season. She worried a year earlier that my being at an all-boys school was stunting my social development. The red flag? Unlike her, I didn’t know how to do the Twist, let alone the Foxtrot and Waltz. Nor, at age 14, did I seem to care. She enrolled me in Dick Chaplin’s dance studio at Preston Center – tough love – and drove me there faithfully from Farmers Branch every Tuesday night, at least once in an ice storm.

She played Uncle Calvin’s 51 times

SHE BELIEVED in education. She wanted to go to college after high school and certainly had the ability, but her father, a crane operator at the Steel Company, did not support that ambition. No one in her family had gone to college at that point, and if anyone did, it wasn’t going to be a woman, her father said. She never forgave him for that. She later earned a two-year associate degree at Richland College, going to classes after work. She helped make it possible for me to go to Brown and later for her two grandchildren, my son and daughter — Devin and Susannah — to attend top colleges. She was generous. She was generous toward her band, too, and shared her appearance fees equally with all who played with her, not typical of someone whose name is on the marquee.

She had talents apart from music. She could sew, really sew. When my dad joined the staff at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (as it was then known) and was expected to attend the beaux arts ball and other classy events, she couldn’t afford to buy a gown from Neiman’s so she made her own – from sheets! You look at photos of those dresses, and they don’t look cheap. They look like they were designed by somebody. Which, of course they were.

Whenever I moved, which was often, the first thing she wanted to know about my new apartment was the dimensions of the windows so she could make curtains. She was always concerned about my living quarters and how she could help improve them. She could have been an interior designer. She had an eye. Which is not to say we always saw eye to eye in this regard. There came a point where I had to say, “Mom, enough with the decorating help. I’m 42 years old.” I moved to New York from L.A. about that time, and I was not yet married. She wanted to come along. “Mom, really? This is not a good look for a grown man, moving to New York with his mother.”

But she was stubborn, harking back to her childhood during the Depression when, as she said, “families helped each other with everything.” Right, well, eventually I gave in because she had been taking care of my dad, who was ill, and I thought she could use a break. I had rented a truck and so on we went to Manhattan in an Isuzu cabover, Mom riding shotgun. I think she composed “The Great K-Mart Singalong” somewhere in Tennessee, and I might have contributed a line or two. Families helping each other with everything.

SHE WORKED 29 years as a secretary for the Dallas office of Eastman Kodak, a company that also did not encourage creative types – or women. The political climate there was such that the day John Kennedy was shot, she noticed her office manager was not at work and thought he probably did it. She wrote a song about wanting to stuff her boss in the paper shredder, but she never gave up that day job until she qualified for a pension.

Still performing at 92: Times Ten Cellars in Lakewood, 2017

She and my dad had both known real financial hardship as children. They were tough in ways that my own generation did not have to be. She had an iron will and determination that I wish I had inherited. My dad brooded – not her. Therapy? What was that? The whole notion was foreign to her, like anxiety itself. That is, until her last years, when she started having some episodes, and I found a therapist for her. I took her to see him four or five times, but it didn’t seem to be helping. I asked her, “Do you want to continue to see Dr. Fogle?”

“I don’t think so,” she said. “He’s a nice man, but he asks me questions, and I don’t want to give the wrong answer.”

“What kind of questions?” I said.

“Like, ‘What’s bothering you?’”

I MOVED to Los Angeles about the time she took the Kodak buyout that allowed her to go full speed into songwriting and performing. So I missed a lot. But she called regularly to keep me informed and report on the latest show she had done with Catch-23, the name she gave to the group backing her up. Catch-23 had different members through the years, but they were all good. Some of them are here tonight. (Would all members of Catch-23 past and present please stand and be recognized?) She attracted fine musicians – including the many who played only on her albums – and you can hear that for yourselves on the compilation CD we’ve put together and are giving out for everyone to take home.

Looking back, she was smart about making a place for herself in the herd of talented pickers and singers who filled the stages of coffee houses and folk clubs in the wake of The Kingston Trio, Joan Baez and Dylan. She did her own thing, writing new lyrics, usually humorous, to the tunes of traditional ballads, in the folk tradition. And though she recorded 11 albums, her best work was in front of an audience.

SHE DREAMED of being on The Tonight Show, and, yeah, that could have happened, but it didn’t. I have no doubt that had the opportunity presented itself, she would have killed, as we say today. She had no fear onstage. She probably should have been on Prairie Home Companion, but that never happened either, for whatever reason. Doesn’t matter now. I want to think she achieved just the right level of acclaim and success, somewhere safely this side of the “big time” in the music business – where she would have needed therapy. She played Uncle Calvin’s 51 times and made it to Musikfest back in her hometown of Bethlehem maybe 10 times. Not counting the hours spent behind an IBM Selectric, helping one boss or another reach his sales quota, she did what she wanted to do and heard a lot of applause.

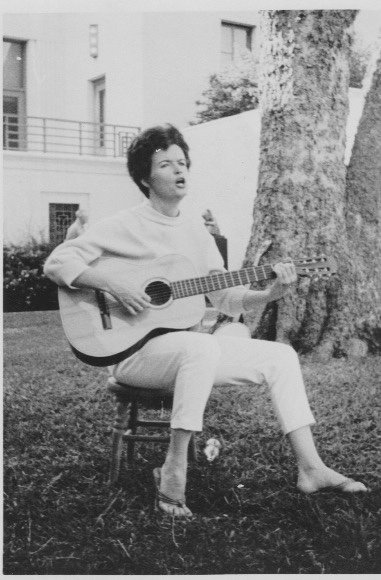

1960s in the DFMA courtyard

On a trip to New York for the Dallas Times Herald in the 1970s, I went to a club to hear a great blues singer and piano player named Alberta Hunter, who was 80 at the time. The notion that Alberta Hunter was, my God, 80, and still performing, was newsworthy. I could not have imagined then that I would one day witness my mother take the stage at age 90, during a birthday concert at Poor David’s Pub.

I had moved back to Dallas by then to help care for her as she became more frail and battled nerve pain in her back and legs. I arrived with the apprehension that any son might have contemplating moving back in with his mother in his 60s – even one who had taught him to play the guitar. And the apprehension was justified. It was not easy. I watched her trademark good cheer being eroded by pain and old age. We argued over many things, including the temperature setting in the house. Sauna level was her default.

SHE PREFERRED donuts and coffee cake to anything nutritious, and my attempts to cook healthy meals for her were mostly in vain. “I’m not a big eater,” she would say as she pushed a bowl of pasta or an omelet aside that she had barely touched. Ten minutes later, after the table was cleared, I would spot her in the kitchen spooning out some ice cream or chocolate pudding. A role reversal had taken place, with me now the parent admonishing the child to eat her vegetables. Which, by the way, she never did. Her defense was always, “Well, I lived to be this age.” What could I say?

When her eyesight got worse, and I said it wasn’t safe for her to be driving anymore, she agreed. But often when she agreed to things, she had her fingers crossed behind her back. One morning a few weeks later, before I was up, I heard a car pull into the driveway. I bolted out of bed and went out to confront her. She had driven just a few blocks to Walmart to get milk, but it had been raining, and I could see muddy tire marks on the lawn.

“Mom, you drove over the lawn,” I said.

“Well,” she said, “I’m out of practice.”

There were unexpected pleasures and challenges in this unplanned reunion of mother and son at this stage of our lives. And I should mention that I got a lot of help from Elizabeth Van Vleck, a former dancer whose artistic sensibilities and compassion Mom could sense the moment they met.

SINCE SHE COULD no longer read, I read to her, something we had never done before and, it occurred to me, represented another role reversal. Both at home and after she moved into assisted living, we read almost every night, a chapter or two at a time, biographies of Leonard Cohen and Paul Simon, folk producer Jim Rooney’s memoir, Maureen Corrigan’s wonderful book about the The Great Gatsby (her favorite novel) and others.

She loved crossword puzzles but needed a partner to read the clues. Despite her memory loss, she was amazing at coming up with correct answers — truly. She figured out words before I did.

We also watched television, though she would have to sit close. Some of her favorites might surprise you. She liked Breaking Bad, Six Feet Under and House of Cards, in addition to historical dramas from the BBC in which sexual relations were portrayed more candidly than in the days of Alistair Cooke.

“Did they sleep together?” she asked me one night. We were watching an episode of Poldark, and Ross, the series’ attractive hero (“He’s so good looking!”), after months of virtuous resistance, had finally taken the comely maid, Demelda, to bed. Unlike the racier Tudors,which she loved, the mechanics were not clear, and with her failing eyes she could not be sure if the romance had been consummated.

AT A YOUNGER AGE, my mother would not have asked me such a question. In fact I would not have been watching shows and movies like this with her. She sang in public about mammograms and the tawdry motel hook-ups of Jimmy Swaggart, but frank talk about sex had never been part of dinner table conversation. Now, in her last years those inhibitions were suspended, and I was hearing pronouncements like, “I don’t think I’d kick him out of bed.” What does a son say to that?

And the news about all her boyfriends! After my return to the family homestead on Eric Lane, she shared with me, for the first time, photos of all the suitors she had before marrying Dad at age 23. Where these photos had been all these years, I have no idea, but now she had them organized in an album, which she reviewed with me on several occasions. “He proposed to me,” she would say, staring at the headshot of a nice-looking guy in uniform. Next page, different guy. “He asked me to marry him.” And next page, “I almost married him,” a guy she said was headed to Harvard after the war – that being World War II. Hmmm. Wonder how that would have turned out? Would she have come to folk music from another direction, in another place – or found a different outlet for her irreverence? Obviously, I would not be standing here if she had picked one of those other guys. But she didn’t. She and my dad had a marriage that lasted 50 years, until his death in 1996.

I’ve told you a lot about her and the many gifts she gave me, including the gift of herself. But the greatest gift was that she was supportive of anything and everything I did. I know not everyone gets that. I’m sure it’s going to take a while for me to get used to her not being here and asking me how my day went and could I bring her some sugar cookies? (The right kind, Pepperidge Farm.)

“Just didn’t want to see that obit,” Tom Adams said – Tom Adams, the Dallas cultural pioneer and a founder of the Texas International Theatrical Arts Society, known as TITAS. I’m sure he echoed the thoughts of many. “She was uncommon,” he said in his email, “You can’t copy that. She fed herself life. She was part of the great family of theater. She was made for the theater — theatrical hair, those oversize glasses. She will be missed.”

“She was, in many ways, ahead of her time,” Mike Granberry wrote in the admiring obit he did for The Morning News. I think he was right, and the proof of that to me is in the number of young women who recognized her in recent years when Elizabeth and I took her out in public — to a play or a concert. They would come over to her wheelchair and say, “Are you Lu Mitchell? I saw you at such and such place in such and such year…” And invariably they would add what an inspiration she had been to them and thank her. That would make her day. And mine, as well.

I ONLY WISH some of those encounters could have been shared across time and space with the nun at Bethlehem Catholic High School who once said to her…“Miss Reiser, we’ll never make a lady out of you.” That nun knew what she was talking about. But she didn’t know the rest.

Mother and son, Oak Cliff, 1951