My Back Pages — and Bob’s

I’ve never met Bob Dylan, but he’s been a major influence in my life, as he has been in the lives of millions of others no doubt. I was reminded of this while watching A Complete Unknown, the biographical film directed by James Mangold, remarkable for the verisimilitude achieved by the young actor Timothee Chalamet who plays the scraggly twenty-something Dylan when he arrived in Greenwich Village from Minnesota in 1961, notably self-possessed and driven to become the next incarnation of Woody Guthrie. We know that he succeeded and then some.

The time span of the film is just the few years Dylan spent in the Village at the beginning of his career, tugged into the spotlight by Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro, in another uncanny performance) and pushed toward “movement” politics by girlfriend Suze Rotolo (Elle Fanning), familiar to us as the girl hugging Bob’s arm on the street scene cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. I suspect the biographical narrative might lack sufficient drama for younger viewers, but for those of a certain vintage, the movie is the richest kind of time travel. Dylan rises to fame in the Village as a gifted folksinger, then risks it all as he heads to the legendary Newport Folk Festival to unveil a new electric sound, much to the consternation of folk purists like Alan Lomax and Pete Seeger, supposedly eliciting boos from the Newport audience.

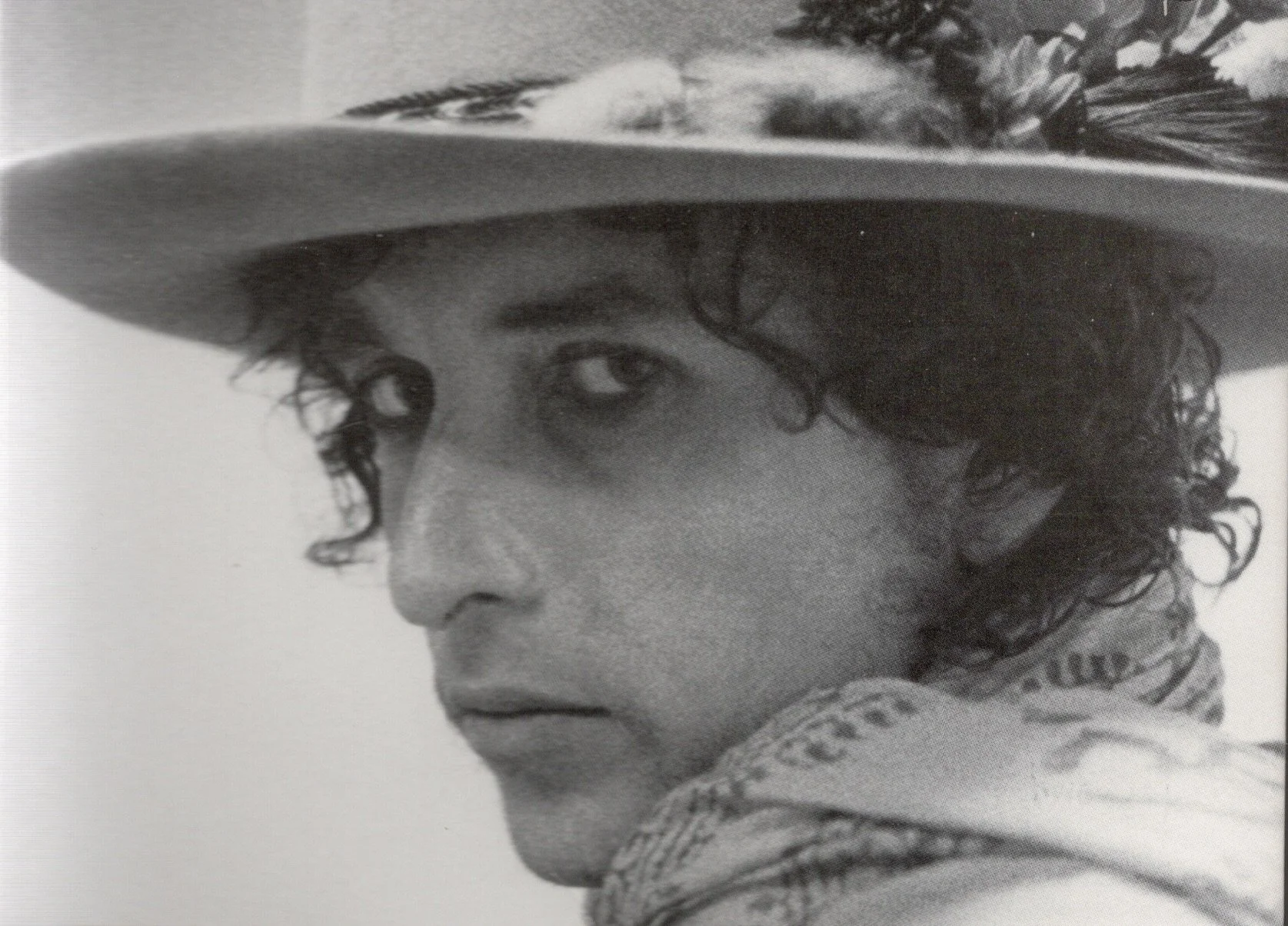

Dylan 1975

Such are the events in A Complete Unknown, based on the book Dylan Goes Electric! by Elijah Wald. The film’s title is taken from a lyric in “Like a Rolling Stone,” the majestically defiant organ-powered anthem released that same summer, blasting Dylan to the top of the charts for the first time. Wait, wasn’t that guy a protest singer?

This is the essence of Mangold’s movie, a character study of the brash future Nobel Prize-winning songwriter who was determined to follow his restive muse and not be constrained by the expectations of others. Considering the way things turned out, it might be hard to recall the disappointment felt by those who loved and admired the Dylan ballads “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and “The Times They Are a Changin’’” and thought he was abandoning acoustic artistry for the crass rewards of rock ‘n’ roll. I remember having those feelings as an earnest young teenager who was attending hootenannies with my mother, herself a budding folksinger and one of the founders of The Dallas Folk Music Society.

The folk revival was in bloom then — significantly all acoustic — and seemed righteously attached to the Civil Rights movement. At the monthly hootenannies, members of the Folk Music Society would show off their discoveries of new songs by Ian & Sylvia, Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Joan Baez and, yes, Bob Dylan. Maybe he was no longer a complete unknown to folkies, but a lot of people still didn’t know how to pronounce his (adopted) last name.

I knew and carried Dylan’s early LPs under my arm to school to share with another young guitar player, David Laney. We learned some of Dylan’s songs and eventually formed a folk quintet of upperclassmen at St. Mark’s to sing and perform them.

I had seen Dylan on TV in 1963, singing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington that culminated in Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream Speech.” With Joan Baez, he performed “When the Ship Comes In,” his rousing metaphorical song about freedom. It was only two years later that he would strap on a Stratocaster at Newport, plug in to the set list from Highway 61 Revisited and change both folk and rock music forever.

The movie ends there without showing what came next: a world tour showcasing his new electric sound, backed by musicians who would become The Band. As it happened, one of the first stops on the tour was Dallas, in the fall of 1965, at SMU’s Moody Coliseum. The local promoter was Angus Wynne III, whose younger brother David was a student at St.Mark’s. David put me in touch with Angus, who managed to suppress a laugh when I asked if he could get me an interview with Bob Dylan. After all, I was the editor of my high school newspaper! Angus said he could get me into the hall during the sound check the day of the show, but the rest would be up to me.

Game on. Hauling a hefty Wollensack reel-to-reel tape recorder and for some reason accompanied by classmate Bill Clarkson (who wasn't even on staff at the paper), I showed up at Moody the day of the concert at 4 p.m. Angus was as good as his word, and Bill and I found our way to the first row of the balcony, where we were spotted by somebody from the stage after only a few songs and summarily booted. So much for my deluded attempt at 17 to interview Bob Dylan. I don’t remember what I was going to ask him, but I do remember that he made his entrance onstage astride a rumbling motorcycle, and when he dismounted, Bill remarked on how skinny he was. “Look at those legs!” Bill exclaimed under his breath. True, one imagined a pop star of his status to be be larger.

Rolling Thunder Revue

I guess that was the closest I ever got to Bob Dylan, whose visionary musical poetry continued to charm and influence me throughout college and after. Over the decades I saw him perform live at least half a dozen more times, starting with his benefit for Ruben Hurricane Carter at the Astrodome in 1976 that I covered as an early assignment for the Dallas Times Herald. I also wrote about the superior set he performed in the Rolling Thunder Revue later that year at Tarrant County Convention Center in Fort Worth. I saw him again in Houston at the Summit in 1981 — maybe the best show of all, which included on that night “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” an early ballad about racial prejudice. In Los Angeles, I saw him in 1986 at the smaller El Rey theater on Wilshire, a relatively intimate venue that lacked seating. I remember because I had to stand for the entire show and I was getting too old for that. Saw him again in L.A. in 1989, outdoors at the Greek Theater, when his compulsive reworking of older tunes had made some unrecognizable. And finally there was the Madison Square Garden shindig in New York City in 1992 when he did three classics (“My Back Pages,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” and “Girl from the North Country”) toward the end of the all-star tribute marking his 30th anniversary with Columbia Records. Columbia subsequently released a 2-CD set documenting the event, which included Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Eddie Vedder, Neil Young, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Tom Petty, and on and on. Unforgettable.

Dylan moved from upstate New York to Southern California in the 1970s. For almost three decades I lived in his vicinity — that is, Los Angeles. But of course L.A is huge, he was ensconced on a bluff overlooking the Pacific in Malibu (far from me) and, in any case, was often on the road. When I lived for a time in West Hollywood in the ‘90s, my jogging course took me past a glass entry door on Doheny that a music industry insider once told me he thought was Dylan’s business office. It was only a rumor, but I wanted to believe it and couldn't help but imagine catching sight of Bob whenever I jogged past. Often I saw rolled up copies of The New York Times and Wall St. Journal on the pavement outside the door but never a person go in or come out.

When I was on staff at the Herald Examiner in Los Angeles in the 1980s, its pop critic was Mikal Gilmore, a reclusive, enigmatic character whose musical acumen was forever validated on the afternoon that Dylan ventured to his non-luxury apartment in Hollywood for an interview. At the underdog Herald Examiner, this was truly a Stop the Presses moment. I wanted to share with Mikal my memory of trying to interview Dylan as a kid back in Dallas, but I never did.

I know it’s unlikely I will ever meet Bob Dylan. Not counting the Mikal Gilmore episode (because I can’t say I really knew Mikal), the best I can do is think about several Six Degrees of Separation connections. One involves my folksinging mom, Lu, who became friends with the Greenwich Village era star Carolyn Hester (and whom I met later in L.A.) and who, history shows, introduced Dylan to Columbia’s John Hammond after Carolyn asked Dylan to play harmonica on an early album of hers. In Dallas I got to know “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” author and maverick Ray Wylie Hubbard and had coffee with him in Santa Barbara the day before he was to record a song with Ringo Starr in L.A. Ringo surely had met Bob, right? There you go. I’m counting only three degrees, maybe two.

Another once-removed brush with “the voice of a generation” (a label he adamantly resisted) involves a story I wrote for the Los Angeles Times Magazine about the roots rocker and eminent SoCal songwriter Dave Alvin who was a good enough guitar player to have moonlighted (anonymously) in Dylan’s band. I went on the road with Alvin for a couple dates in 1999, and our conversation the first day yielded what became the opening line of the story: “Dave Alvin wonders what it’s like to be Bob Dylan while I wonder what it’s like to be Dave Alvin.” The Sunday that “Dave Alvin: the King of California” was published in the Times, I learned that the single reference to Dylan had earned the story a link in a daily Dylan website called Expecting Rain that detects every mention of Bob at any time anywhere in the English language media. I checked and, yeah, Expecting Rain (from a lyric in “Desolation Row”) is still rocking after all these years: forty-three links to stuff about Bob Dylan today you can check out if you’re interested.