The Accommodation

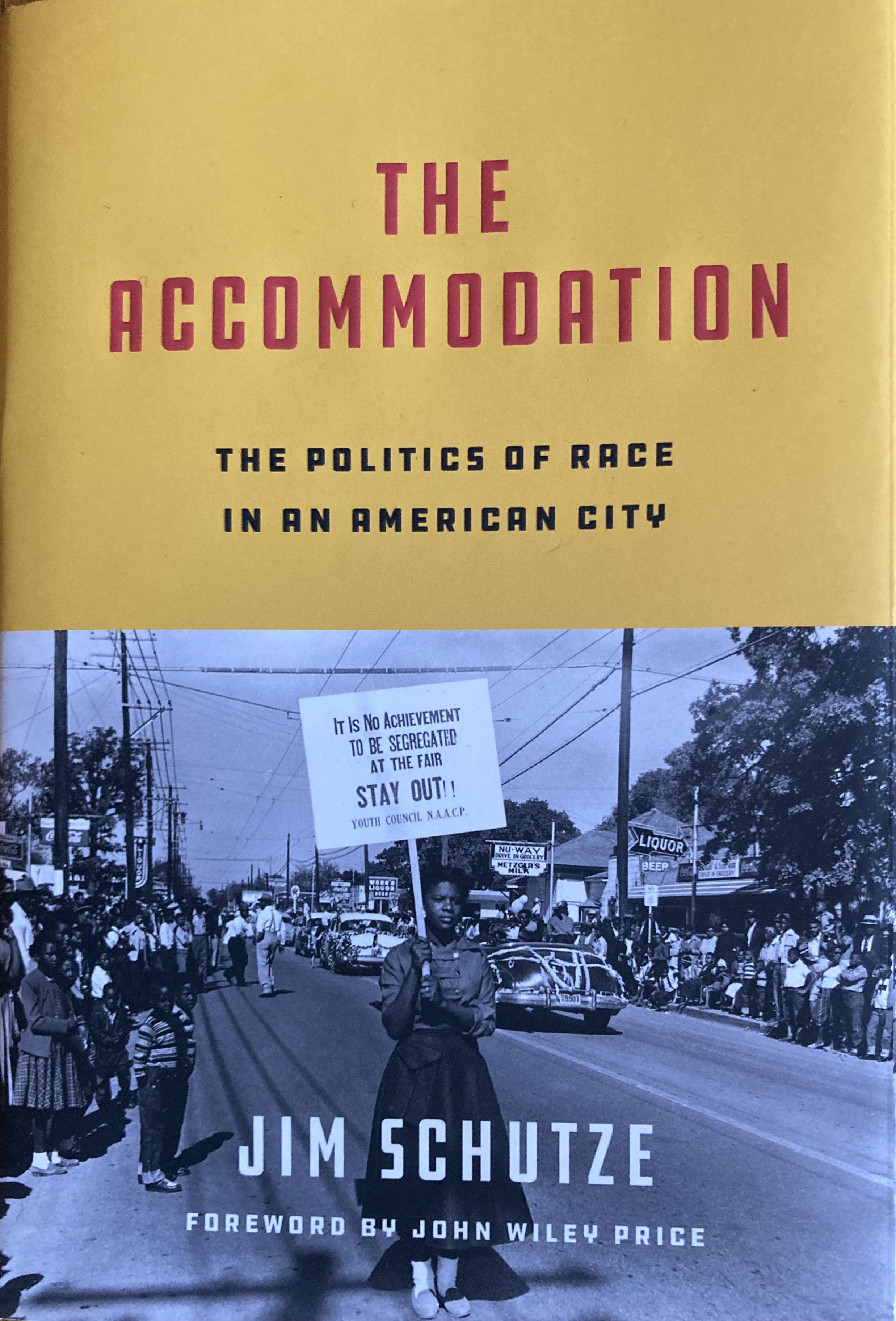

I WAS in California when my former Times Herald colleague Jim Schutze’s book about the history of race relations in Dallas, The Accommodation, was published in 1986. I don’t remember even hearing about it — or how it was mysteriously suppressed and not published by Dallas’ Taylor Publishing at the last minute. What was that about? Subsequently, I learned that the book had been published eventually in New Jersey, but for some reason very few copies existed, and by now those had attained the status of valuable contraband, shared privately by journalists and other traders in hidden truth.

So when Dallas’ Deep Vellum publishers announced it had reached a deal to republish the book last fall, 35 years later, I knew I would read it. It’s a stunner, a career-defining triumph for Schutze and a belated indictment of the city’s oligarchic racism that managed to keep the Civil Rights Movement at bay in Dallas for decades. No wonder the business elite and perhaps the Dallas Morning News did not want this shameful history made public.

It’s embarrassing to learn that Black homeowners were bombed out of neighborhoods where they weren’t wanted in the 1940s and ’50s; that the city government, time and again, seized Black-owned housing via eminent domain, paying the homeowners a fraction of the land’s worth; that Blacks were only allowed attend the State Fair on “Nigger Day” until 1953; that department stores in Dallas prohibited Blacks from trying on clothing; that influential First Baptist Church pastor W.A. Crisswell thundered against integration from the pulpit; that the white-managed Black Ministers Alliance gave Martin Luther King, Jr. short shrift when he came to town early on; that advocates for truly integrating the schools were branded as communists by civic leaders; that District Attorney Henry Wade made sure a grand jury investigating those neighborhood bombings would not reveal who the plotters were. And on and on.

THROUGH IT ALL, the Dallas Citizens Council, led by plutocrats like former mayor R.L. Thornton, shrewdly kept the peace, such as it was, making accommodation with the Black ministers to avoid violence and public protests — until finally the attempt to drive Blacks out of the neighborhoods around Fair Park led to the federal court order implementing single member city council districts, dismantling the old guard’s rigged system. That didn’t happen until 1978.

Schutze sees a menacing congruence in the “patriotic” rhetoric hurled at the art museum in the 1950s for its exhibitions of “red art,” the angry mob that surrounded U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson (spitting on him) in downtown Dallas in 1963 and the ways the Morning News reviled the Kennedys and suggested that defiant Black leaders were communists.

“Only now,” Schutze writes here (in 1986), “has Dallas even started to be able to admit to itself what it had worked so hard to deny and repress all those years: that Dallas did kill Kennedy. Not deliberately, not conspiratorially. For years, the Dallas Morning News was so eager to prove that nobody in Dallas had been in on it that that the paper became the main engine driving the cult of conspiracy surrounding the assassination, passing on any and every conspiracy theory it could lay its hands on — as long as the conspirators hadn’t been members of the Dallas Citizens Council.”

FILLING IN the big picture, he reminds us of the thinly veiled hostility to Martin Luther King expressed by former Governor John Connally, who said after King’s murder five years later, “He contributed much to the chaos and the strife and the confusion and the uncertainty in this country, but whatever his actions he deserved not the fate of assassination.” That was just Texas talking, Schutze points out. Ironically it had been Connally’s resistance to the civil rights legislation championed by the Kennedys that had brought JFK to Dallas in the first place. And to his death.

This is history worth knowing. Maybe it’s not surprising that Taylor Publishing, best known for producing high school yearbooks, caved to pressure to yank The Accommodation from its presses 35 years ago. But I’d love to know more details about that — the who, what and why, conspicuously absent from John Wiley Price’s foreword to the new edition and the news stories I’ve seen about it. Seems like a big story about how power is exercised in Dallas, the very thing Schutze wrote about in the book itself — so well.